Trent Toone, Deseret News

They have set that example, that tradition, and you see the work they have done. You find the need to follow that example. You know you can do it because others have done it. A lot of other family members haven’t endured, but you can help them.—Rios Pacheco

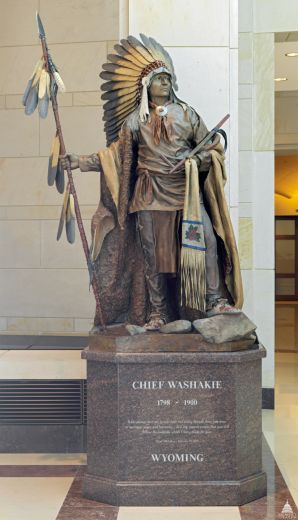

It’s difficult to fathom what the Shoshone chief had already endured.

Sagwitch had witnessed the near annihilation of the Northwestern Shoshone, including members of his own family, and was wounded at the hands of U.S. troops at the Bear River Massacre in 1863. He watched as their lands were stolen and his people were cheated and treated as an inferior race. They suffered destitution and were often days from starvation.

Yet in 1873, when a compelling dream instructed the tribal leaders to join The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and drastically change their lifestyle, Sagwitch peacefully, humbly and courageously led his band in a new direction.

They not only survived, but in time, they thrived.

“Because he continually fought for a peaceable solution, he and his tribe ended up having a future,” said Scott R. Christensen, a historian and author.

Tuesday, Jan. 29, marks the 150th anniversary of the Bear River Massacre. On that day, tribal descendants, family, friends and community members will gather at the massacre site for a commemoration ceremony at 11 a.m. As that event approaches, Darren B. Parry, vice chairman of the Northwestern Band of the Shoshone Nation and a direct descendant of Sagwitch, continues to marvel at his ancestor’s valiant faith, a series of significant events that resulted in blessings and how the gospel of Jesus Christ helped his people find hope and the ability to forgive in the aftermath of the massacre.

“Accepting the gospel saved us … ,” Parry said.

The massacre

In response to friction between American Indians and white travelers, Col. Patrick Edward Connor and about 200 California volunteers attacked the winter camp of the Northwestern Shoshone near today’s Preston, Idaho, before dawn on a bitterly cold Jan. 29, 1863. With inferior weapons and large numbers of mothers, children and aged adults, the Shoshone were overmatched.

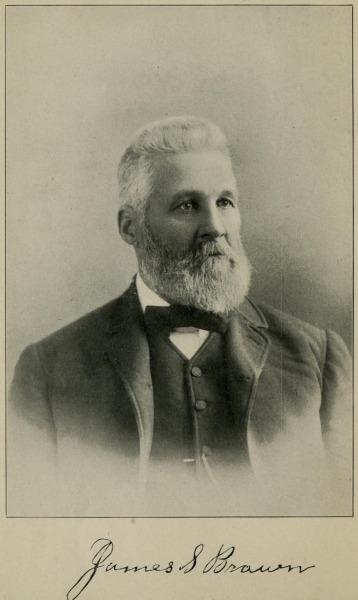

“A lopsided battle became a wholesale slaughter,” Christensen wrote in his book, “Sagwitch: Shoshone Chieftain, Mormon Elder, 1822-1887.”

What unfolded that day was horrific. The soldiers brutally killed children, defiled women, burned the Indians’ homes, stole their supplies and walked away with their horses, according to historians. When it was over, more than 300 had perished, making the Bear River Massacre the single greatest loss of Indian lives in American history.

Connor lost 17 men, although many more were wounded or had frostbite. Connor was promoted to brigadier general as a result of his victory.

Sagwitch was one of the survivors. He was shot twice in the hand before he hid in the Bear River among the brush and frozen chunks of ice. Three of his sons also survived, including 2-year-old Beshup Timbimboo, who was wounded several times by troops. The little boy wandered the battlefield, still clutching a bowl of frozen pine nut gravy, until family members found him.

A dream, a missionary and many baptisms

For the next 10 years, the Northwestern Shoshone struggled to survive amid poverty and a tug-of-war with government officials over their lands and resources.

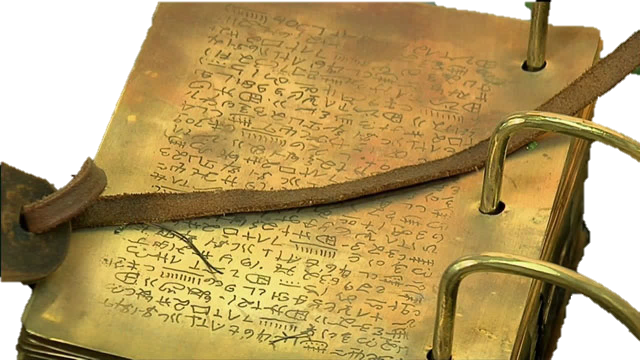

In early 1873, one of Sagwitch’s fellow chiefs had a vision in which three men visited him. One of the three messengers told him “that the Mormon’s God was the true God … that he and the Indian’s Father were one; that he must go to the Mormons and they would tell him what to do; that he must be baptized, with all his Indians; and that the time was at hand for the Indians to gather, stop Indian life, and learn to cultivate the earth and build houses,” according to Christensen’s biography of Sagwitch.

All the chiefs believed the dream was the will of the Great Spirit. They also found common ground with various aspects of the Latter-day Saint religion, such as healing by the laying on of hands. They went looking for George Washington Hill and found him in Ogden.

Hill had previously developed a trusted relationship with the Indians as a missionary. He spoke their language. They requested that Hill, whom they called “Inkapompy” — “Man with Red Hair” — come and preach to them.

Hill wanted to help them but first needed LDS Church President Brigham Young’s permission. A few days later, Hill was summoned to the prophet’s office, where he was called to be a missionary to the Indians. President Young also charged Hill with helping the people establish a place where they could learn to farm and be self-supporting.

On May 5, 1873, Hill boarded a train for Corinne and upon arrival continued walking the 12 miles to the Shoshone camp. Somehow Sagwitch knew Hill was coming and the people were prepared to receive him. Hill commenced teaching the gospel and by the end of the day, he had baptized and confirmed 102 individuals. The next day, Hill wrote to Brigham Young, “(I) never felt better in my life nor never spent a happier day.”

Less than a week after their baptisms, Sagwitch and three others met with President Young and were ordained as elders in the Melchizedek Priesthood. In 1875, Sagwitch and his wife received their temple endowments in the Salt Lake Endowment House and were sealed together by President Wilford Woodruff.

“In that era, you about had to be called to a bishopric or high council to receive the Melchizedek Priesthood,” Christensen said. “Clearly, they were seen as important converts and people who would grow into their church membership.”

After Sagwitch and his people joined the church, missionary work among the American Indians exploded.

Over the next four years, nearly 1,200 were baptized in the Bear River, including members of various bands and tribes throughout the Intermountain West. They buried their weapons of war and became peaceful, faithful members of the church. “‘We ask forgiveness for our sins and bad deeds,’ they said,” wrote the late Mae Timbimboo Parry, Sagwitch’s great-granddaughter and tribal historian. “ ‘We want to start a new way of life.’ This they did.”

A new life

Over the next few years, the Shoshones adapted to a new lifestyle. They attempted to establish farms and homes near Corinne and Tremonton before finally settling at Washakie in Northern Box Elder County. Hill was with them every step of the way as their teacher, advocate and protector, with additional support from the church and its members. Homesteading laws were utilized to allow the Shoshone to remain on their ancestral lands without being required to move to the reservation at Fort Hall, Idaho. The Indians were also allowed to hunt and gather food as long as it didn’t interfere with the harvest.

“The government tried to get us moved to Fort Hall, but Brigham Young said not on your life,” Parry said. “They are Mormons.”

Legacy of devotion

In 1880, an LDS ward was established in the Indian colony at Washakie.

“The only English had to be the sacrament prayers, but everything else on the Sabbath was in Shoshone,” Christensen said. “The white administrators had to learn the language or wonder what was going on.”

The members at Washakie proved to be among the most faithful in the church. They dedicated countless hours to the construction of the Logan Temple by learning to mix mortar and haul stones from the quarries using their ponies, among other jobs. After the temple was dedicated, the Indians were among the first to perform work for their kindred dead.

Through the years, the Indians also manifested their devotion through a high level of church attendance and generous payment of tithing and offerings.

The Washakie ward was one of very few units to register 100 percent compliance in a 1922 churchwide drive titled “Every member a tithepayer,” Christensen said.

After his death in 1887, Sagwitch’s descendants displayed a strong commitment to their LDS faith. Beshup Timbimboo, also known as Frank Timbimboo Warner, the 2-year-old massacre survivor with seven wounds, became one of the first Native Americans to be sent out as a proselytizing missionary. He served three missions.

Soquitch, Sagwitch’s oldest son, served as a priesthood leader in the Washakie Ward for many years. He had a special calling to visit the homes of the Shoshone and give priesthood blessings to the sick.

Yeager Timbimboo, another son who survived the massacre, served in various leadership callings. In 1926, Yeager was invited by President Heber J. Grant to speak in general conference at the Salt Lake Tabernacle. His remarks were translated by his bishop, Elder George M. Ward.

“Since I have accepted this gospel,” Yeager said on that occasion, “I have felt to be a friend to this people, and I have no desire to kill, or do anything wrong that would displease the Spirit of the Lord.”

“Imagine hearing that in general conference today,” Parry said.

In 1939, Yeager’s son Moroni Timbimboo was ordained by Apostle George Albert Smith as bishop of the Washakie Ward — the first Native American to hold that ecclesiastical position. Numerous other descendants have also served missions or filled various positions in the church.

“After everything he (Sagwitch) had been through … by one man accepting the gospel, thousands of lives, including mine, were changed,” Parry said. “I couldn’t have done it.”

During World War II, the government drafted several of the young men at Washakie into active service. It also employed a good number of residents as civilian defense workers at Hill Field, the Ogden Air Depot and other nearby military installations, Christensen said.

“The Shoshone people at Washakie had significant skills. They were readily hired because they were such good workers. They weren’t stuck on a reservation so they were available,” Christensen said. “It gave them a completely different future compared to their relatives at Fort Hall. Many were also retained after World War II.”

Prior to the dedication of the Brigham City Temple in 2012, artists Linda Christensen and Mike Malm, with help from Cheryl S. Betenson, painted a mural depicting missionaries and a group of Indians during a baptismal confirmation on the banks of the Bear River in the 1870s.

The colorful mural now hangs in the Brigham City Temple baptistry as a fitting tribute to the American Indians and missionary work.

“The painting is a beautiful work of art,” Christensen said. “It represents the cooperation of two peoples in the settlement of Box Elder County and the establishment of service in the temple in northern Utah. It’s a wonderful, full-circle moment to see that event from the 1870s acknowledged in that temple, which is located just a few blocks from the Northwestern Shoshone tribal headquarters.”

Gratitude, forgiveness

Today there are more than 500 members of the Shoshone Nation living primarily in Box Elder, Weber and Davis counties, Parry said. Considering the high unemployment and suicide rates found on Indian reservations, Parry reiterated his gratitude for the gospel and how events unfolded after the massacre.

“Accepting the gospel, I think, saved our posterity from being raised on a reservation,” Parry said. “The prophecy about the Lamanites blossoming as a rose (D&C 49:24) … I believe it has started, but greater things are still to come. There is still work to do.”

Rios Pacheco’s ancestor, Sarah Tickpatecky, survived the massacre by hiding in the brush by the river. To keep from being discovered by the soldiers, she was forced to smother her crying baby daughter to death and let her body float away down the river. Her husband was also killed. She eventually remarried and was among those baptized on May 5, 1873.

She persevered through the years despite many hardships, lived an honorable life and endured to the end.

Today, Pacheco honors her and his other ancestors by serving in the church and community. He finds continual strength in the noble examples of his forebears.

“You look into your heritage,” Pacheco said. “They have set that example, that tradition, and you see the work they have done. You find the need to follow that example. You know you can do it because others have done it. A lot of other family members haven’t endured, but you can help them.”

Pacheco also says forgiveness comes in living the teachings of the gospel.

“The church teaches us to overcome hatred. True conversion means finding forgiveness,” Pacheco said. “The family I come from has set that example.”